The County of East Lothian or Haddington is a shire on the south coast of the Firth of Forth and the North Sea.

The sea washes the county’s long shoreline of 41 miles; to the north the Firth of Forth and, rounding the corner at Dunbar, to the northeast is the North Sea. To landward, on the west and southwest is Midlothian and to the south and southeast is Berwickshire.

Many of the towns and villages by the coast serve as a commuter belt for Edinburgh and have grown large as a result. Outside the towns though the gentle hills provide fine farming. Other towns, in particular North Berwick and Dunbar are seaside resorts of the gentler sort.

The county town is Haddington, lying inland.

Geography

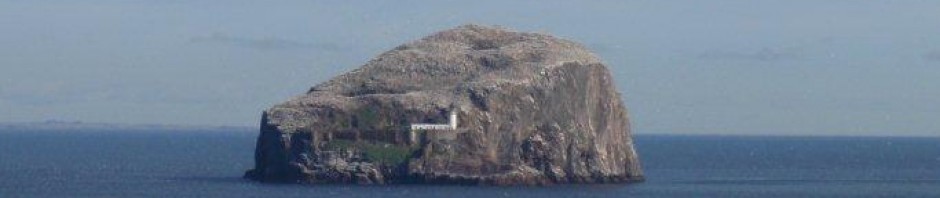

The coast stretches for 41 mile along the shoulder of the county. Offshore, the Bass Rock and Fidra Isle in the Firth of Forth belong to the shire, and there are numerous rocks and reefs off the shore, especially between Dunbar and Gullane Bay. Dunbar has a high, rocky headland, long a place of defence: its shattered castle stands over the harbour.

Broadly speaking, the northern half of the shire slopes gently to the coast, and the southern half is amongst the Lammermuir Hills, dividing the Lothians from the Middle Shires. Several peaks of Lammermuir exceed 1,500 feet, and here is the county’s highest point: Meikle Says Law (1,755 feet), on the boundary with Berwickshire.

The more level tracts of the north are still broken by notable hills; Traprain Law (724 feet in the parish of Prestonkirk), North Berwick Law (612 feet), and Garleton Hill (590 feet, to the north of Haddington).

The only important river is the Tyne, which rises to the southeast of Borthwick in Midlothian, and, taking a generally north-easterly direction, reaches the sea just beyond the park of Tynninghame House, after a course of 28 miles, for the first 7 mile of which it belongs to Midlothian, the rest of its course to East Lothian. It is noted for a very fine variety of trout, and salmon are sometimes taken below the linn at East Linton. The Whiteadder rises in the parish of Whittingehame, but, flowing towards the south-east, leaves the shire and at last joins the Tweed near Berwick.

There are no natural lakes, but in the parish of Stenton is found Pressmennan Loch, an artificial sheet of water of somewhat serpentine shape, about 2 miles in length, with a width of some 400 yds., which was constructed in 1819 by damming the ravine in which it lies. The banks are wooded and picturesque, and the water abounds with trout.

Geology

The higher ground in the south, including the Lammermuir Hills, is formed by shales, greywackes and grits of Ordovician and Silurian age; a narrow belt of the former lying on the north-western side of the latter, the strike being southwest to northeast The granitic mass of Priestlaw and other felsitic rocks have been intruded into these strata. The lower Old Red Sandstone has not been observed in this county, but the younger sandstones and conglomerates fill up ancient depressions in the Silurian and Ordovician, such as that running northward from Oldhamstocks towards Dunbar and the valley of Lauderdale. A faulted-in tract of the same formation, about a mile in breadth, runs westward from Dunbar to near Gifford. Carboniferous rocks form the remainder of the county.

The Calciferous Sandstone series, shales, thin limestones and sandstones, is exposed on the south-eastern coast, but between Gifford and North Berwick and from Aberlady to Dunbar it is represented by a great thickness of volcanic rocks consisting of tuffs and coarse breccias in the lower beds, and of porphyritic and andesitic lavas above.

These rocks are well exposed on the coast, in the Garleton Hills and Traprain Law; the latter and North Berwick Law are volcanic necks or vents. The Carboniferous Limestone series which succeeds the Calciferous Sandstone consists of a middle group of sandstones, shales, coals and ironstones, with a limestone group above and below.

The coal-field is synclinal in structure, Port Seton being about the centre; it contains ten seams of coal, and the area covered by it is some 30 square miles.

Glacial boulder clay lies over much of the lower ground, and ridges of gravel and sand flank the hills and form extensive sheets.

Traces of old raised sea-beaches are found at several points along the coast. At North Berwick, Tynninghame and elsewhere there are stretches of blown sand. Limestone is worked at many places, and hematite was formerly obtained from the Garleton Hills.

History

Of the famed Gododdin of these lands, known to the Romans as the tribe of the Votadanii, little trace remains beyond a few Old Welsh elements in place names and their fortifications; circular camps are found at Garvald and Whittinghame and hill forts, notably on Traprain law. Few traces remain in East Lothian either of the Roman occupation.

After the Romans retreated, the Gododdin kingdom thrived for a century or two before being subdued by the incoming English, the Bernicians whose kingdom united with its southern neighbour to become the Kingdom of the Northumbrians. It is to the Northumbrians that much of the county is owed; the place-names are almost all English. Dunbar (Dynbaer) was the seat of a Northumbrian Ealdorman (and Bishop Wilfred was imprisoned here by the king around 680).In those days the lands of the Lothians were known by the Anglo-Saxons as Loðen, which encompassed all the land north of the River Tweed. The name though is ancient, believed to date from the days of the Gododdin. In the tenth century, or possibly 1018, the Lothians and their people were joined to Scotland.

This county emerges early in history; the early twelfth century Charters of that great reformer King David I refer to grants in Hadintunschira (and variant spellings), and it appears to have been a prosperous and important shire.

Haddingtonshire was comparatively prosperous until the civil wars of the houses of Bruce and Baliol, and the constant strife with the Kings of England caused by the Auld Alliance. Its place on the road from England to Edinburgh brought armies this way time out of mind.

Through Haddingtonshire came James IV in September 1513 on his last, mad invasion of England that ended in the slaughter of the King and the flower of Scotland at Flodden Field, and here 40 years later came the forces of Henry VIII of England as he began the “Rough Wooing” – seeking by force to win a marriage treaty between two children; his son Edward and Mary Queen of Scots. The last battle of this island’s fratricidal wars, the last ever between the Kingdoms of Scotland and England, was fought just over the boundary in Midlothian, at Pinkie Cleugh.

The shire was not to be sure of peace until the union of the crowns in 1603, but even so all was not quite over as the Wars of the Three Kingdoms broke out and Cromwell came here, victorious at Dunbar in 1650. As the 1745 Jacobite rebellion pressed south from the Highlands, at Prestonpans in 1745 the rebels won the field to secure the road to Edinburgh. That though was the last battle and thereafter East Lothian was allowed to blossom and prosper.

In the Victorian Age, the railways came here. Forging lines to Edinburgh, the North British Railway Company linked the towns and villages of East Lothian. (They too took the time to rename a town; Linton became ‘East Linton’ to avoid confusion with ‘West Linton’ in Peeblesshire. The main line ran (as it still does) between Edinburgh and Berwick but branches were sent off at Drem to North Berwick, at Longniddry to Haddington and also to Gullane, at Smeaton (in Mid-Lothian) to Macmerry, and at Ormiston to Gifford, providing a grant county network and enabling the easy traffic of men and produce across the county. At the same time such seaside resorts as North Berwick could flourish and take their current form.